Love, in its myriad forms, has inspired poets across centuries to capture its essence in verse. From the raptures of new romance to the ache of loss, from quiet devotion to passionate longing, the language of love finds its most potent expression in poetry. Classic love poems, in particular, offer a timeless window into the human heart, revealing emotions and experiences that resonate just as deeply today as they did when they were written.

Contents

- 10. “Since There’s No Help,” by Michael Drayton (1563-1631)

- 9. “How Do I Love Thee,” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

- 8. “Love’s Philosophy,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

- 7. “Love,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

- 6. “A Red, Red Rose,” by Robert Burns (1759-1796)

- 5. “Annabel Lee,” by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

- 4. “Whoso List to Hunt,” by Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

- 3. “To His Coy Mistress,” by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

- 2. “Bright Star,” by John Keats (1795-1821)

- 1. “Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds” (Sonnet 116), by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

- The Enduring Legacy of Classic Love Poems

These poems, often steeped in rich language, formal structures, and profound insights, stand as enduring monuments to the power and complexity of love. They explore love’s idealism, its challenges, its joys, and its inevitable encounters with time and mortality. Reading them allows us to connect with the universal human experience of loving and being loved, offering comfort, understanding, and inspiration. They are not merely historical artifacts but living testaments to the enduring power of emotional connection.

For centuries, poets have sought to articulate the ineffable feelings that love stirs within us. The “classic” status of these poems is earned not just through age, but through their lasting impact, their artistic mastery, and their ability to speak to fundamental truths about the human condition. Exploring this rich heritage helps us understand the evolution of both poetic form and emotional expression. While modern love poems offer contemporary perspectives, classic love poems provide a foundational language and depth that continues to enrich our understanding of this profound emotion. They remind us that while the world changes, the heart’s capacity for love remains a constant. These works provide a valuable touchstone for anyone seeking to understand love through the lens of some of history’s greatest literary minds.

10. “Since There’s No Help,” by Michael Drayton (1563-1631)

Beginning a list of Love Poems Classic with a poem about the end of an affair might seem counterintuitive, but Michael Drayton’s sonnet “Since There’s No Help” offers a powerful depiction of love’s vulnerability and the pain of parting. Written by a contemporary of Shakespeare, this sonnet captures the complex emotional transition from feigned indifference to desperate pleading. Drayton initially presents a facade of stoicism, declaring, “Nay, I have done, you get no more of me,” suggesting a clean break and emotional detachment. This opening couplet sets a tone of finality, almost defiance, attempting to assert control over a painful situation.

However, this outward show quickly dissolves as the sonnet progresses into its sestet. Here, the true depth of the speaker’s despair is revealed through a vivid personification of love and its associated virtues. Love is depicted as dying, its “pulse failing,” while “Passion speechless lies,” “Faith is kneeling by his bed of death,” and “Innocence is closing up his eyes.” This allegorical scene elevates the personal heartbreak to a tragic, almost mythological event. By portraying these abstract concepts as dying figures, Drayton emphasizes the profound and multifaceted nature of the loss. It’s not just a relationship ending; it’s the death of hope, trust, and purity associated with that love. The speaker’s final lines reveal the desperate hope that, even at this terminal moment, the beloved’s kindness might yet revive the dying love, highlighting the lingering attachment and the painful realization of irreparable loss. This sonnet is a poignant reminder that classic love poems encompass the full spectrum of love, including its sorrowful conclusions.

### Since There’s No Help

Since there’s no help, come let us kiss and part;

Nay, I have done, you get no more of me,

And I am glad, yea glad with all my heart

That thus so cleanly I myself can free;

Shake hands forever, cancel all our vows,

And when we meet at any time again,

Be it not seen in either of our brows

That we one jot of former love retain.

Now at the last gasp of Love’s latest breath,

When, his pulse failing, Passion speechless lies,

When Faith is kneeling by his bed of death,

And Innocence is closing up his eyes,

Now if thou wouldst, when all have given him over,

From death to life thou mightst him yet recover.9. “How Do I Love Thee,” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

Perhaps one of the most famous and widely quoted love poems classic, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 43 from Sonnets from the Portuguese is a powerful declaration of boundless affection. Addressed to her future husband, Robert Browning, the poem is a direct response to his implied question, “How do I love thee?” Browning’s answer is an enumeration, or “counting,” of the ways her love manifests, reaching into the deepest parts of her soul and extending to the highest ideals.

The sonnet employs hyperbole to express the intensity and pervasiveness of her love. She loves “to the depth and breadth and height” her soul can reach, using spatial metaphors to suggest the vastness of her feeling. This spiritual dimension is further emphasized by the connection to her “ends of being and ideal grace,” suggesting a love that is intertwined with her very existence and moral aspirations. The poem moves from the abstract to the concrete, detailing how she loves him in the mundane moments of “every day’s Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.” This anchors the transcendent love in the reality of daily life, showing its constant presence. She contrasts this quiet need with the passionate intensity drawn from “old griefs” and connects it to the innocent certainty of her “childhood’s faith,” replacing “lost saints” with the beloved. The cumulative effect is a love that is spiritual, mundane, passionate, innocent, pure, and free. The concluding lines express a hope that this love will not only continue but intensify beyond death, if “God choose.” The sonnet’s enduring popularity lies in its directness, its sweeping declaration, and its comprehensive portrayal of love as an all-encompassing force.

### How Do I Love Thee?

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.8. “Love’s Philosophy,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Love’s Philosophy” is a short but charming lyric poem that presents a persuasive argument for physical intimacy through appeals to nature. While titled “Love’s Philosophy,” the poem’s “philosophy” is less a deep exploration of love’s nature and more a playful, almost syllogistic argument for connection based on the observed behaviors of the natural world. The speaker points to various natural phenomena that mingle and unite: fountains mingle with rivers, rivers with the ocean, winds with heaven, mountains kiss high heaven, waves clasp one another, and sunlight clasps the earth.

The core argument is presented through rhetorical questions. If “Nothing in the world is single” and “All things by a law divine In one spirit meet and mingle,” then why, the speaker asks, should he and his beloved remain separate? The poem relies on the pathetic fallacy, attributing human actions like “kissing” and “clasping” to natural elements, thereby creating a picture of a universe constantly seeking union. The final rhetorical question, “What is all this sweet work worth / If thou kiss not me?” is a direct plea, framing the beloved’s refusal as a violation of this universal “law divine.” The poem is a classic example of Romantic persuasion, using the perceived harmony and interconnectedness of nature as a mirror for the desired human connection. Its lightness and persuasive charm make it a popular choice among love poems classic.

### Love’s Philosophy

The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the ocean,

The winds of heaven mix for ever

With a sweet emotion;

Nothing in the world is single;

All things by a law divine

In one spirit meet and mingle.

Why not I with thine?—

See the mountains kiss high heaven

And the waves clasp one another;

No sister-flower would be forgiven

If it disdained its brother;

And the sunlight clasps the earth

And the moonbeams kiss the sea:

What is all this sweet work worth

If thou kiss not me?7. “Love,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Love” is a longer, narrative poem that explores the relationship between storytelling, emotion, and romantic connection. Unlike Shelley’s concise argument, Coleridge employs a ballad form, a traditional narrative structure often used for tales of love, loss, and the supernatural. The speaker recounts how he won the love of his beloved, Genevieve, not through direct declaration or philosophical argument, but by singing her a moving story. The setting is romantic and atmospheric – midway on a mount beside a ruined tower, under moonshine and twilight.

The core of the poem is the story within the story: a tale of a knight who loved a lady, endured suffering, and died in her arms after saving her. The speaker sings this “old and moving story,” noting that Genevieve “loves me best, whene’er I sing The songs that make her grieve.” This suggests a connection between shared emotional experience, even sorrow, and the deepening of love. As he tells the story, focusing on the knight’s pining and eventual tragic end, his voice becomes “faultering,” interpreting his own love through the narrative of another. Genevieve is visibly affected, showing “a flitting blush,” “downcast eyes,” and eventually weeping with “pity and delight,” blushing with “love, and virgin-shame.” The emotional resonance of the ballad awakens a complex mix of feelings in her. The poem culminates in her yielding to her emotions, half-enclosing him with her arms and confessing her love. Coleridge’s poem highlights the power of shared narrative and emotional vulnerability as a pathway to romantic union, showcasing a different facet of love poems classic – love born from shared sensibility and affective experience.

### Love

All thoughts, all passions, all delights,

Whatever stirs this mortal frame,

All are but ministers of Love,

And feed his sacred flame.

Oft in my waking dreams do I

Live o’er again that happy hour,

When midway on the mount I lay,

Beside the ruined tower.

The moonshine, stealing o’er the scene

Had blended with the lights of eve;

And she was there, my hope, my joy,

My own dear Genevieve!

She leant against the arméd man,

The statue of the arméd knight;

She stood and listened to my lay,

Amid the lingering light.

Few sorrows hath she of her own,

My hope! my joy! my Genevieve!

She loves me best, whene’er I sing

The songs that make her grieve.

I played a soft and doleful air,

I sang an old and moving story—

An old rude song, that suited well

That ruin wild and hoary.

She listened with a flitting blush,

With downcast eyes and modest grace;

For well she knew, I could not choose

But gaze upon her face.

I told her of the Knight that wore

Upon his shield a burning brand;

And that for ten long years he wooed

The Lady of the Land.

I told her how he pined: and ah!

The deep, the low, the pleading tone

With which I sang another’s love,

Interpreted my own.

She listened with a flitting blush,

With downcast eyes, and modest grace;

And she forgave me, that I gazed

Too fondly on her face!

But when I told the cruel scorn

That crazed that bold and lovely Knight,

And that he crossed the mountain-woods,

Nor rested day nor night;

That sometimes from the savage den,

And sometimes from the darksome shade,

And sometimes starting up at once

In green and sunny glade,—

There came and looked him in the face

An angel beautiful and bright;

And that he knew it was a Fiend,

This miserable Knight!

And that unknowing what he did,

He leaped amid a murderous band,

And saved from outrage worse than death

The Lady of the Land!

And how she wept, and clasped his knees;

And how she tended him in vain—

And ever strove to expiate

The scorn that crazed his brain;—

And that she nursed him in a cave;

And how his madness went away,

When on the yellow forest-leaves

A dying man he lay;—

His dying words—but when I reached

That tenderest strain of all the ditty,

My faultering voice and pausing harp

Disturbed her soul with pity!

All impulses of soul and sense

Had thrilled my guileless Genevieve;

The music and the doleful tale,

The rich and balmy eve;

And hopes, and fears that kindle hope,

An undistinguishable throng,

And gentle wishes long subdued,

Subdued and cherished long!

She wept with pity and delight,

She blushed with love, and virgin-shame;

And like the murmur of a dream,

I heard her breathe my name.

Her bosom heaved—she stepped aside,

As conscious of my look she stepped—

Then suddenly, with timorous eye

She fled to me and wept.

She half enclosed me with her arms,

She pressed me with a meek embrace;

And bending back her head, looked up,

And gazed upon my face.

‘Twas partly love, and partly fear,

And partly ’twas a bashful art,

That I might rather feel, than see,

The swelling of her heart.

I calmed her fears, and she was calm,

And told her love with virgin pride;

And so I won my Genevieve,

My bright and beauteous Bride. Samuel Taylor Coleridge portrait

Samuel Taylor Coleridge portrait

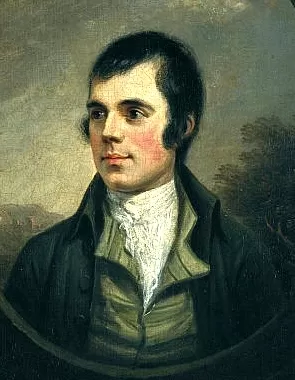

6. “A Red, Red Rose,” by Robert Burns (1759-1796)

Robert Burns’ “A Red, Red Rose,” also known by its first line, “O my Luve is like a red, red rose,” is a quintessential example of a simple, yet profoundly moving, declaration of love. Written in the Scots dialect, the poem uses vivid, accessible metaphors to express the speaker’s deep affection and commitment. The opening simile compares the beloved to a “red, red rose” that’s “newly sprung in June,” evoking freshness, beauty, and vibrant life. The second simile likens her to a “melody That’s sweetly played in tune,” suggesting harmony and pleasure.

These initial images establish the beloved’s beauty and the delight she brings. The poem then escalates into grand declarations of eternal devotion. The speaker pledges his love will last until impossible events occur: “Till a’ the seas gang dry” and “Till a’ the seas gang dry… And the rocks melt wi’ the sun.” These hyperbolic expressions underline the absolute and unwavering nature of his love. He vows to love her “While the sands o’ life shall run,” grounding the cosmic scale of his devotion in the finite reality of human life, yet still emphasizing its endurance. The final stanza introduces the context of parting (“fare thee weel, my only luve!”), but immediately follows with a promise of return, no matter the distance (“Though it were ten thousand mile”). The poem’s structure, moving from simple comparison to extravagant vow and concluding with a promise of steadfastness despite separation, creates a powerful and memorable expression of enduring love. Its lyrical quality and heartfelt emotion have made it one of the most beloved love poems classic.

### A Red, Red Rose

O my Luve is like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve is like the melody

That’s sweetly played in tune.

So fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry.

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun;

I will love thee still, my dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel awhile!

And I will come again, my luve,

Though it were ten thousand mile.5. “Annabel Lee,” by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee” is a hauntingly beautiful narrative poem that explores the themes of intense, childhood love and the tragic grief following the death of a beloved. While focused on loss, the poem is fundamentally a testament to the extraordinary nature of the love shared between the speaker and Annabel Lee. Set in a “kingdom by the sea,” the poem establishes a dreamlike, almost fairy-tale atmosphere, emphasizing the purity and intensity of their bond from a young age. The speaker repeatedly stresses that their love was “more than love,” envied even by the winged seraphs of heaven.

This supernatural jealousy is presented as the cause of Annabel Lee’s death: a wind blows “out of a cloud, chilling” her. This personification of the wind as an agent of death, driven by envious angels, adds a layer of dark romance and cosmic tragedy to the personal grief. Despite her death and being shut up “in a sepulchre,” the speaker insists that their love was stronger than that of wiser, older individuals and could not be “dissever[ed]” by angels or demons. The poem then shifts to the speaker’s unending devotion and grief. He finds no respite, dreaming of her nightly when the moon beams and feeling her eyes in the stars. The poem culminates in his ritual of lying by her side in her tomb by the sea, emphasizing the depth of his despair and his inability to let go of their connection, even in death. Poe’s mastery of musical language, repetition, and rhythm creates a hypnotic effect, drawing the reader into the speaker’s obsessive grief. While tragic, it is a powerful portrayal of a love so profound it defies death and separation, securing its place among love poems classic.

### Annabelle Lee

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea:

But we loved with a love that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee;

With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven

Laughed loud at her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsman came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven,

Went laughing at her and me—

Yes!—that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud by night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the laughter in heaven above,

Nor the demons down under the sea,

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.4. “Whoso List to Hunt,” by Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

Sir Thomas Wyatt’s “Whoso List to Hunt” is a poignant sonnet of frustrated desire and resigned withdrawal, often interpreted as an allegory for his pursuit of Anne Boleyn, who was unattainable due to her relationship with King Henry VIII. The poem is a powerful example of early Renaissance lyric poetry in England, showcasing the adaptation of the Petrarchan sonnet form. It opens with the speaker pointing out the object of his desire – a “hind” (female deer) – to others (“Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind”), but immediately states his own inability to continue the chase (“But as for me, alas, I may no more”).

The metaphor of hunting the deer serves as an extended conceit for the pursuit of the elusive beloved. The speaker admits the pursuit has left him “wearied… sore,” yet he cannot withdraw his “wearied mind” from her. He follows “Fainting,” acknowledging the futility, “Since in a net I seek to hold the wind.” This simile beautifully captures the impossibility of possessing the desired woman. The poem shifts in the sestet, offering advice to others who might attempt the pursuit. He warns them their efforts will be “in vain.” The reason for her unattainability is then revealed: she wears a collar inscribed with “Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am,” a phrase echoing Christ’s words after resurrection (“Touch me not”) and asserting ownership by “Caesar,” understood here as the King. The addition “And wild for to hold, though I seem tame” further emphasizes her elusive nature and the danger of the pursuit. This sonnet is a remarkable exploration of forbidden love, unrequited passion, and the pain of surrender, making it a significant entry among love poems classic.

### Whoso List to Hunt

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But as for me, alas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Since in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

“Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.”3. “To His Coy Mistress,” by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” is a complex and celebrated poem that, while framed as a seduction attempt, delves into profound themes of time, mortality, and carpe diem (seize the day). It’s a masterpiece of metaphysical poetry, known for its intellectual argument, witty conceits, and striking imagery. The poem is structured as a formal argument in three parts, often likened to a syllogism.

The first section (“Had we but world enough and time…”) envisions an idyllic courtship free from the constraints of time. The speaker hyperbolically describes an age-long devotion, praising each part of the beloved’s body with vast spans of time, suggesting a love that would patiently and meticulously explore her beauty. This section establishes the premise of infinite time, contrasting it with the reality. The second section (“But at my back I always hear…”) introduces the terrifying reality of mortality. Time is personified as a “wingèd chariot hurrying near,” and the speaker starkly depicts the inevitability of death, where beauty fades, honour turns to dust, and desire to ashes in the grave. The grim image of “worms shall try That long preserved virginity” is a stark reminder of the physical decay that awaits, powerfully undermining the logic of prolonged chastity. The third section (“Now therefore, while the youthful hue…”) presents the conclusion. Since time is limited and death is certain, the lovers should seize the present moment. The language shifts from leisurely praise to urgent action: “Now let us sport us while we may.” The final couplet, “Thus, though we cannot make our sun / Stand still, yet we will make him run,” encapsulates the poem’s philosophy – while they cannot stop time, they can live so intensely that they make time rush past them. While its focus is persuasion for physical love, its powerful meditation on time and mortality makes it a compelling, albeit unconventional, entry in the realm of love poems classic.

### To His Coy Mistress

Had we but world enough and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

We would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long love’s day.

Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side

Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide

Of Humber would complain. I would

Love you ten years before the flood,

And you should, if you please, refuse

Till the conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable love should grow

Vaster than empires and more slow;

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze;

Two hundred to adore each breast,

But thirty thousand to the rest;

An age at least to every part,

And the last age should show your heart.

For, lady, you deserve this state,

Nor would I love at lower rate.

But at my back I always hear

Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Thy beauty shall no more be found;

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing song; then worms shall try

That long-preserved virginity,

And your quaint honour turn to dust,

And into ashes all my lust;

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace.

Now therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy skin like morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires

At every pore with instant fires,

Now let us sport us while we may,

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour

Than languish in his slow-chapped power.

Let us roll all our strength and all

Our sweetness up into one ball,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Through the iron gates of life:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.Readers interested in how form influences meaning in poetry might find exploring types of haiku helpful, as the strict structure of haiku contrasts sharply with the sustained argument of Marvell’s poem.

2. “Bright Star,” by John Keats (1795-1821)

John Keats’ “Bright Star, would I were stedfast as thou art—” is one of the most famous sonnets in English literature, a late work by the Romantic poet that exquisitely balances cosmic perspective with intense personal desire. Written possibly as a dedication copy to his beloved, Fanny Brawne, the sonnet expresses a wish to possess the unwavering permanence of a star, but not in its solitary, detached state. The octave describes the star’s constant vigil over the natural world – the washing of the shores, the falling snow – portraying a grand, but isolated, existence. The speaker initially desires this “stedfast” quality, but immediately qualifies it with “No—yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,” rejecting the star’s lone splendour.

The turn (volta) in the sonnet occurs at the beginning of the sestet, dramatically shifting the focus from the distant star to the intimate physical presence of the beloved. The speaker wishes to be steadfast not in isolation, but in perpetual physical connection: “Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast.” The desired constancy is no longer a remote, observational state but an intensely sensual and immediate experience – to “feel for ever its soft fall and swell,” “Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,” and “still to hear her tender-taken breath.” The poem culminates in a powerful expression of ultimate desire: to “so live ever—or else swoon to death.” This final line presents an absolute choice – eternal, sensuous union or the complete oblivion of death. It’s a testament to the Romantic ideal of transcending ordinary life through the intensity of love and sensation. The sonnet’s blend of cosmic imagery and intimate physical detail, combined with its fervent emotional plea, cements its status among quintessential love poems classic.

### Bright Star

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.1. “Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds” (Sonnet 116), by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

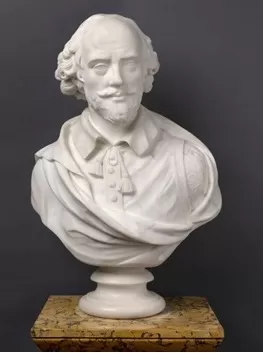

William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 stands as perhaps the most profound and enduring definition of love in the English language. Unlike many of his other sonnets which address specific individuals or situations, Sonnet 116 aims for a universal, almost philosophical definition of true love. It opens with a strong assertion: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments.” This sets the tone for a poem that seeks to define love by what it is not and then by what it is.

The poem systematically dismisses common understandings of love that are contingent or transient. True love, according to Shakespeare, is not something that “alters when it alteration finds” or changes when the beloved changes (“bends with the remover to remove”). It is not susceptible to external pressures or internal shifts in circumstance or feeling. Instead, love is defined by its steadfastness and permanence. It is described using powerful metaphors of constancy: “an ever-fixed mark” (like a navigational beacon or star) that is unshaken by storms (“tempests”). It is “the star to every wand’ring bark,” a reliable guide whose true “worth’s unknown” even as its position is fixed.

The sonnet then confronts the ultimate test of time. Love is explicitly stated as “not Time’s fool,” meaning it is not subject to the ravages of time, unlike physical beauty (“rosy lips and cheeks”) which falls within Time’s “bending sickle’s compass.” True love “alters not with his brief hours and weeks, / But bears it out even to the edge of doom.” It endures until the end of existence itself. The concluding couplet serves as a powerful affirmation of the speaker’s definition: “If this be error and upon me proved, / I never writ, nor no man ever loved.” This stakes the very existence of his poetry and the reality of human love on the truth of his definition. Sonnet 116 offers an ideal of love that transcends physical attraction and temporal change, focusing on a spiritual and intellectual union of “true minds.” Its elegant structure, timeless message, and powerful metaphors make it arguably the most iconic among all love poems classic.

### Sonnet 116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand’ring bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.The concept of love explored here, particularly Shakespeare’s idea of an “ever-fixed mark,” can be seen reflected in various poetic forms and themes. For instance, exploring haiku themes reveals how poets compress complex emotions and observations into minimalist structures, offering a different lens on universal feelings like love or the appreciation of nature. Sometimes, even within the strict constraints of haiku, themes of love emerge, as seen in examples of haiku poem love.

The Enduring Legacy of Classic Love Poems

These ten poems represent a diverse collection of love poems classic, spanning different eras, styles, and perspectives. They offer insights into the multifaceted nature of love as understood by some of the greatest poets in the English language. From the dramatic sorrow of Drayton’s parting to the boundless declarations of Barrett Browning, from Shelley’s playful persuasion to Coleridge’s narrative seduction, from Burns’ simple sincerity to Poe’s tragic obsession, from Wyatt’s bitter resignation to Marvell’s urgent argument, and from Keats’ sensual idealism to Shakespeare’s timeless definition – each poem contributes a unique voice to the chorus of human experience with love.

What makes these poems enduring is their ability to articulate feelings that are both intensely personal and universally recognizable. They use language with precision and power, employing meter, rhyme, metaphor, and structure to create effects that resonate emotionally and intellectually. Studying these works provides not only a deeper appreciation for the art of poetry but also a richer understanding of the complex ways in which love has been perceived, experienced, and expressed throughout history. They remind us that the pursuit, joy, pain, and constancy of love are threads that connect us across time and culture, ensuring the continued relevance of these classic voices. Exploring these poems can be a deeply rewarding experience, offering solace, inspiration, and new ways to think about our own relationships and emotions. Whether dissecting the structure or simply allowing the language to wash over you, these classic poems provide a rich source of reflection on one of life’s most central themes.